Blackcap © Andrew Mart

The Blackcap’s winter presence in 161 tetrads, almost one quarter of the county, illustrates an amazing story of rapid adaptability. Contrary to the frequent comments, these are not birds that have ‘stayed’ for the winter. Our wintering Blackcaps are immigrants from breeding areas in southern Germany and Austria which have migrated north-west. When they arrive here, they find a relatively mild climate, and an even warmer urban micro-climate; provision of food in gardens also helps them to survive. In spring, they have a shorter return migration than their conspecifics that have wintered in Africa, and so arrive back on their central European breeding grounds earlier and in better condition, thus being able to claim the best territories and breed earlier. It is easy to see how such an advantageous trait can become established and flourish.

The habitat codes show that most birds recorded (69%) were in human (F) habitats, with 15% in broadleaved or mixed woodland and only 5% in scrub, with 8% in farmland hedgerows. They penetrate even into urban areas, with five records in F1 habitats, 76 in suburban (F2) and 34 in rural areas (F3). Clusters of records around urban areas show up obviously on the map, especially at Macclesfield, Congleton, Wilmslow, Warrington, Northwich, Crewe, Nantwich, Chester, and the Wirral towns. Blackcaps do not seem to call in winter, though, thus being not easy to detect, so a bias towards records from gardens and well-watched places is to be expected.

For a period of seven years in the 1990s, the county bird reports noted the sex of all wintering Blackcaps, totalling significantly more males (255) than females (172). There is, however, no significant difference in the sex ratio of birds ringed in the winter period from 1981 to 2006 by members of Merseyside Ringing Group, so perhaps there are equal numbers present but the males are just more visible to observers. Many of the county’s annual bird reports comment that fewer birds are recorded in mild winters. It is not known if this indicates that there are fewer Blackcaps wintering in the county, or if this observation derives from hard weather driving some birds into gardens from where most of the records come.

They take a wide variety of food, including natural foods, especially the most nutritious fruit – berries of Cotoneaster,holly, honeysuckle and ivy – as well as almost any food provided at a bird-table. Many observers comment on their aggression at communal feeders, and they are well able to hold their own with resident British birds. The national survey in 1978/ 79 – a very cold winter – recorded them taking especially bread, fat, apples and peanuts, plus an eclectic range of items of household scraps (Leach 1981).

Coward and Oldham had ‘no evidence that it ever winters in Cheshire’, and it seems that Boyd recorded the first, on 23-25 January 1944 near Northwich (Country Diary), closely followed by another on 30 January 1944 at Cotebrook (Country Diary). He had never seen one in his Great Budworth parish (Country Parish). It is difficult to tell from the literature when the habit of Blackcaps wintering became more common. Bell (1962) states that ‘there are no recent Cheshire records’ but the first Cheshire Bird Report in 1964 gave the species’ status as ‘winter resident, rare’ and recorded three ‘winter’ birds during that year (two in early November), without any particular comment.

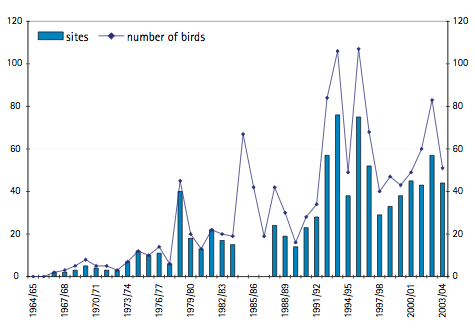

Blackcap wintering numbers.

The chart summarise records each winter from the start of the Cheshire Bird Report in 1964. There are some problems in interpreting the reports, not least because some years’ reports jumble the early- and late-winter records. It is always difficult to adjudge the status of late-staying or early-arriving summer migrants, and many records are published without dates. From 1964, birds in November and March were counted as ‘winter’, but from 1975 onwards, November birds were declared to be late migrants. In recent years, with an increased population of birds and birdwatchers, and much extended dates for spring and autumn migration, there is no clear division between breeding or passage birds and those wintering here. With all of those caveats, the chart attempts to count only birds within our defined winter period (16 November to end of February).

Annual records started in 1966/67, but stayed in single figures each winter until 1974/75. The spike in 1978/79, caused by a national survey of the species (Leach 1981), suggested that casual reporting under-estimated their numbers by about a factor of two. From then numbers rose gradually through the 1980s, but more or less reached a plateau from 1992/93 onwards, averaging about 60 birds recorded per winter, although with large year-to-year fluctuations. This Atlas has clearly stimulated a higher level of recording, and the likely total of birds each winter in the county is certainly in three figures.

Sponsored by Bernard Machin