About the Atlas

During the three breeding seasons 2004–06 and three winters 2004/05–2006/07, Cheshire and Wirral Ornithological Society (CAWOS) organized more than 350 volunteers to survey all of the county, trying to find every species of bird that was breeding or wintering. The basis for survey was the 2 × 2 km square of the Ordnance Survey grid, a standard recording unit for many local biological Atlases with an area of 4 km2, called a tetrad. There are 670 tetrads in the county for the breeding season and 684 for winter, the latter including some offshore areas with no permanent land area, thus being unsuitable for breeding birds but occupied by seabirds and waterfowl at various states of the tide. Fieldworkers recorded birds throughout Cheshire and Wirral, covering every suitable habitat within each tetrad. This is the county’s second breeding bird Atlas, starting 20 years after the end of the previous Atlas for which fieldwork ran from 1978 to 1984, but there has been no previous survey in winter at the tetrad scale.

In the breeding season, species were observed carefully and their behaviour noted according to a hierarchy of 16 codes indicating different levels of breeding status: these translated into categories of possible, probable or confirmed breeding (see overleaf). Surveyors were urged to try to achieve as high a level of breeding status as possible, with the ideal being one of the ‘two-letter’ codes representing a variety of behaviour consistent with proof of breeding. A total of 34,516 unique records (only one record of a species per tetrad in any of the three years) were collected, of 153 species.

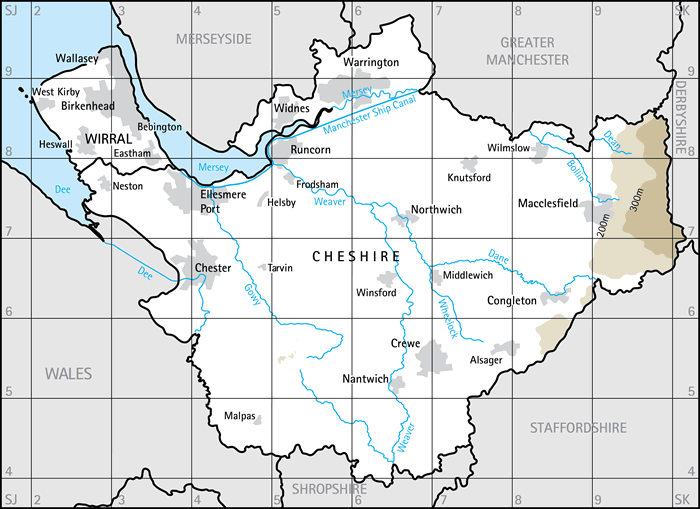

Cheshire and Wirral, showing the main conurbations, rivers and canals, and land lying above 200 m and 300 m in altitude.

In winter, the aim was to record every species that was using the tetrad, where possible including some additional information on the size of flocks or roosts; birds flying over but not using the tetrad were excluded from the Atlas. The winter period was intended to avoid periods of migration and breeding and, to make an Atlas sensible, to cover the time when most birds were settled in one area. Having the same dates for all species, regardless of their biology, inevitably entails a compromise, and ‘winter’ was defined as 16 November to the end of February. In winter, 34,237 unique records (only one record of a species per tetrad in any of the three winters) were submitted, of 183 species.

This Atlas aimed to provide a complete record of birds

in every area of Cheshire and Wirral in the breeding

and wintering seasons. Photos © Peter Twist.

To increase the value of the data for conservation, habitat information was also collected, with observers for every record, breeding or winter, allocating one or more habitat codes according to the standard system devised by the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO). This is, we believe, a feature that has not been incorporated into previous Atlases, but proved to be straightforward to do and has provided much new information of great interest for many species. The section ‘Cheshire and Wirral and its habitats for birds’ includes a listing of these codes and discussion of the county’s habitats.

As well as recording distribution and habitats, it was felt important to measure the abundance of the county’s birds. For the scarce breeding species it usually proved possible either to count the known nest sites or to assess from the number of occupied tetrads. For the more common and widespread species we achieved estimates of breeding population from results of the Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) in the county. This is a simple system based on observers walking two 1 km transects twice during the breeding season, counting every bird seen or heard. The BBS scheme was devised by the BTO to monitor year-to-year changes in bird populations, and has been used nationally since 1994 at more than 3,500 sites. In Cheshire and Wirral, the results from BBS in 2004 and 2005 have been used to calculate, in collaboration with the BTO, breeding populations for 65 species. This is the first time that this technique has been used at a county level. A further unique feature of this work is that maps of abundance across the county have been generated for 35 species.

The population figures are expressed as the number of individuals. The relationship between this figure and that for breeding pairs depends on the birds’ behaviour, and differs between species depending on the relative detectability of males and females and the proportion of non-breeders (Newson et al. 2008). The populations are quoted with the statistical confidence limits in brackets, within which there is a 95% probability that the true value lies.

We had hoped to be able to assess the abundance of birds in winter but this is a much more difficult task—most birds are not territorial, many of them flock and many are silent—and there is no established methodology. So, this was the one aspect of the original objectives that was not fulfilled. However, 63% of winter records were accompanied by a count of the largest flock seen, allowing for the first time realistic estimates of populations of some of the wintering birds in the county.

Species accounts make up the bulk of this book. They concentrate on putting the Atlas results in context, describing the species’ distribution within the county and, where possible, their abundance; changes in breeding distribution from our First Atlas; national changes in population and distribution; and links to habitat and conservation. For the breeding season, the former status in the county has been well described in our First Atlas and is not repeated here. As this is the first wintering bird Atlas of Cheshire and Wirral, the winter texts place the present results against the background of previous published work in the county.

Although the subject is birds, this is a ‘People’s Atlas’! All of the participants were amateurs, volunteering to do this work in their spare time; the term ‘citizen science’ is better established in the USA than in Britain, but endeavours like this Atlas are perfect examples of the engagement of citizen scientists. Even though every surveyor was an amateur, we have tried to maintain the highest professional standards in the work, and we believe that this Atlas stands alongside the best of all local projects to date.

More of the results of this Atlas are given elsewhere on this website, and more detail of the organization and methodology of the Atlas on the Methodology and results pages.