Great Tit © Ben Hall

Great Tit is the eighth most widespread species across Cheshire and Wirral. This Atlas showed a very similar distribution to our First Atlas, with birds almost everywhere except for three of the highest-lying tetrads at the east of the county, Hilbre and the estuaries, and a handful of others where they were not found. This species’ division across the habitat classes was almost identical to that of Blue Tits. Most recorded habitats were woodland (374 tetrads) or human sites (333), with fewer in scrub (85 tetrads), hedgerow (129) and farmland (131).

This is an easy species in which to prove breeding (89% of records) and provided the third highest number of confirmed breeding records. Fieldworkers in 281 tetrads saw parties of recently fledged young, usually noisy and conspicuous as they pester their parents for food. Adults carrying food or a faecal sac were reported in 146 tetrads, but occupied or used nests were recorded in 22 tetrads, and a nest with eggs or chicks in 133. Nests were reported from natural sites including holes in oak, alder and birch trees, in numerous nest-boxes and a variety of others including an old Kingfisher hole in a stream bank, holes in walls, gate posts, telegraph poles, a road signpost and a metal lamp-post on Runcorn East station (SJ58K). These metal structures must suffer extremes of temperature, but chicks fledged from at least some of them. This is probably the species most likely to interrupt postal services by nesting in a post box, as Tricia Thompson reported from near Styal (SJ88H).

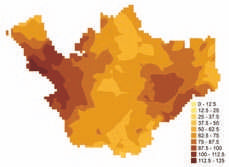

Great Tit abundance.

The BTO BBS analysis shows that the breeding population of Cheshire and Wirral in 2004-05 was 104,160 birds (87,940-120,430), corresponding to an average of about 85 pairs per tetrad with confirmed or probable breeding, and about 1.8% of the UK breeding population of 5.8 million birds (Newson et al 2008). Great Tits nationally have increased by about 22% in the twenty years since our First Atlas, probably encouraged by more provision of winter food in gardens and the lack of hard weather to knock them back.

The Great Tit is often said to be the most studied small bird in the world: their breeding has been followed for sixty years in woods near Oxford and for seventy years in the Netherlands (Perrins 1979, Gosler 1993). Their egg-laying dates are proving to be a sensitive and fascinating test of climate change. In Cheshire woodlands, they usually start laying in the second half of April, but can be somewhat earlier or later; Great Tits in gardens breed earlier but raise smaller broods. The laying date of British birds has advanced by about a week in the last forty years, in line with rising temperatures, but the date for emergence of winter moth caterpillars, the chicks’ main food, has not shifted as much. In the Netherlands, however, the opposite is true: caterpillar emergence is earlier and Great Tit laying phenology has stayed the same (Visser & Both 2005). In both cases the result is the same: they are increasingly struggling to find enough food for their brood.

Sponsored by Paul S. Lewis