Pheasant © Ben Hall

Largely ignored by most birdwatchers, and once voted the most hated bird in Britain, there is a strong argument for saying that Pheasant is in fact England’s most important bird as its requirements have shaped much of the English countryside (Marchington 1984). Many wooded areas and hedgerows exist mainly to provide cover for this species. Lest the foregoing be taken as suggesting that the introduction and rearing of Pheasants has had a benign or positive influence on the countryside, however, it should be noted that some authors report potentially negative effects of high Pheasant densities on native UK birds. These include the structure of the undergrowth and woodland field layer and the spread of disease and parasites (Fuller et al. 2005). Interspecific competition for food could be an issue as well: at around 1kg, rather more for males and less for females, the biomass of Pheasants exceeds that of any other British bird.

There are some self-sustaining populations of wild birds but the species’ numbers are determined principally by releases of reared birds for shooting: the Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust estimated in the early 1990s that some 20–22 million birds were released in the UK each autumn. This figure has increased four-fold since the mid 1960s (Tapper 1999), and nowadays may well be higher still. About one-in-ten of the released birds are expected to survive until spring, when they must form the major part of the breeding population. The corresponding figures for Cheshire and Wirral are not known but the BTO BBS analysis shows that the breeding population of the county in 2004-05 was 9,420 birds (5,810-13,030). Most of those detected on BBS transects were males, which are much more vocal with their far-carrying ‘kor-kok’ calls, and more visible as the brightly-plumaged birds strut about their territories whilst the camouflaged females are hidden on their nests. However, each year roughly half of all males are not breeding because many dominant birds gather a harem of several females and mate with each of them, leaving a surplus of unmated, mostly one-year-old, males, although some birds do nest as conventional pairs.

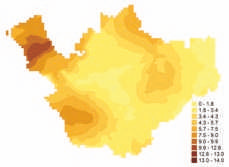

Pheasant abundance.

The maps show that Pheasants have spread considerably since our First Atlas, with a net gain of 130 tetrads, and they are now found almost everywhere apart from urban areas. The most noticeable increases have been in north and west Wirral, east of Macclesfield, and a broad swathe through the centre of Cheshire, roughly following the lines of the rivers Weaver and Gowy. The national population index rose by 57% from 1984 to 2004 and the county population has probably risen substantially from the First Atlas estimate of ‘from two to five pairs per occupied tetrad’; the current figure corresponds to an average of about 17 birds per tetrad in which the species was recorded. It seems inappropriate to use ‘pairs’ for a species with such a flexible mating system. Most of the records of confirmed breeding came from observations of one or more adults with a brood of chicks (159 tetrads), but surveyors in 25 tetrads found nests, in various stages of occupation.

Pheasants can be found in almost any habitat: two-thirds of the records for this Atlas were farmland, of all types, with woodland (19%), scrub (6%) and semi-natural grassland (4%). They feed in the open, often in field margins, yet remain close to shelter. Favoured areas for cover are protected from wind and weather, and provide suitable nesting areas: most nests are near to the edge of a wood or its internal rides.

Sponsored by Robin Hart